When the outgoing Kyrgyz ambassador to the US invited me to join him at his farewell reception in January, I gladly accepted. Attending a gathering at Blair House–the US president’s guest house–was a first for me. I was doubly honored when Ambassador Kadyr Toktogulov thanked me by name during his remarks.

And I was completely surprised by what I heard next.

“Did you study in Moscow in the 1980s?” a man standing near me asked.

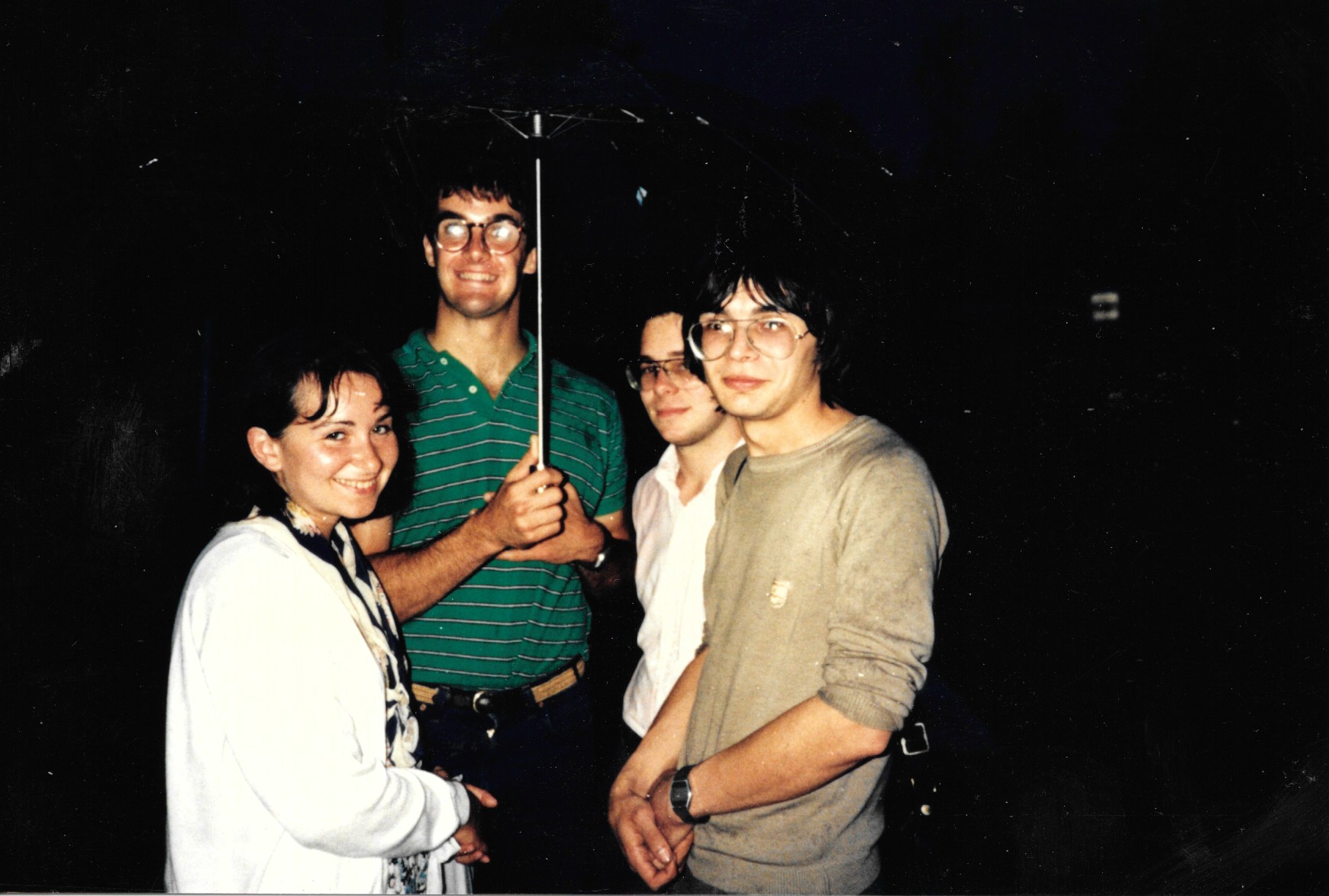

We recognized each other immediately. Tom Firestone and I had been exchange students in 1985 in Moscow on a summer Russian language program that is the predecessor to the Advanced Russian Language and Area Studies Program, one of American Council’s longest running and most respected programs.

Memories from 34 years ago flooded back. It was a historic period: Moscow at the start of perestroika, young and dynamic Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev coming to power, and controversial laws restricting when Soviet citizens could buy vodka.

And how could I forget the poster above Tom’s bed of US President Ronald Reagan? Under Reagan’s portrait was the phrase in Russian: A man with strong convictions. Reagan at that time was confronting the USSR with a military buildup, part of his “Peace through Strength” approach to the Soviet Union.

That summer Tom and I were among 100 US college students studying Russian for six weeks at the Pushkin Institute in Moscow. We lived across the hall from one another in a Soviet hotel that served as our dormitory. We were adventurous and curious, making Soviet friends and becoming wise to survival in a non-market economy. In fact, the Soviet Union then was an alternate universe, where money didn’t matter. Instead, it was connections, influence, and appetite for risk-taking that set someone apart. Of course, speaking Russian helped too. It was a fascinating summer of discovery.

We met young Soviet Jews ready to emigrate to the US and the first Soviet entrepreneurs or “fartsovschiki” who made handsome–and illegal–profits changing money on the black market. A popular saying in Moscow then was: “If you don’t take risks, you won’t drink champagne.” Everywhere we went, we were met with Russian hospitality, even when our hosts had little to offer.

Tom and I caught up quickly at Blair House. He is now a partner in the law firm Baker McKenzie. After finishing law school, he took a job investigating the Russian mafia in New York City. He then worked at the US Embassy in Moscow as the representative of the US Justice Department. I told Tom of my career as a journalist, living in Russia and covering Russian-speaking teams at three Olympics, before turning to international development work and writing books.

Bringing us together at the ambassador’s farewell reception was Tom’s support in organizing the US-Kyrgyzstan Business Council and my work with the Kyrgyz Embassy to promote my book about Kyrgyzstan, "Have the Mountains Fallen." Much of the research for that book was done in Russian. In fact, it was the Kyrgyz ambassador’s mention of my name in connection with the book that caused Tom to turn his head that day at Blair House.

So, it turned out both of our lives have been shaped by the study of Russian. We’ve seen and experienced personally the highs and lows of US relations with Russia and other countries in Eurasia over the past decades. Because of our professions, we have both lived close to a decade in Russian-speaking countries, earning our livelihoods and making lifelong friends through our connection to the Russian language.

Yet, as I reflect, I understand that learning Russian has enriched me in other ways. Odd as it may sound, it has allowed me to become a different person. When I speak Russian, I separate from my American upbringing and my position in my family, which were forged through speaking English. When expressing myself in Russian, I speak more directly because that’s the way the language is. I lower my voice at times, particularly for certain Russian phrases. My sense of humor and irony in Russian springs from my life experiences in Russian-speaking countries, whether it be through reading literature, socializing, watching movies or reading the news. So, my life is richer because I can be two people: my English-speaking self and my Russianized persona.

I promised to send Tom photos of our time in Moscow. We have a lot to catch up on.

About the Author

Jeff Lilley is director of monitoring and evaluation at American Councils for International Education. A former educator and journalist, he has 15 years of experience managing democracy and governance programs and is himself an alumnus of a two Russian language study abroad programs. He has worked in Russia, Central Asia and the Middle East. Jeff is also the author of two books, a family memoir titled "China Hands," published in 2004, and most recently "Have the Mountains Fallen," a non-fiction account of the Cold War in Central Asia, published in 2018.

Contact the Author